Metal Fume Fever, often dubbed “welders’ disease” or “brass founders’ ague,” is a common, yet frequently misunderstood, occupational illness resulting from the inhalation of fine metal fumes. This condition predominantly affects individuals working in industries where metals are heated to high temperatures, such as welding, galvanizing, smelting, and casting. While generally considered benign and self-limiting, the symptoms can be debilitating and easily mistaken for other illnesses, leading to misdiagnosis and unnecessary concern. Understanding its causes, symptoms, and, crucially, its prevention is paramount for safeguarding the health of workers in at-risk professions.

What is Metal Fume Fever?

Metal Fume Fever (MFF) is a temporary flu-like illness that occurs after exposure to freshly generated metal oxide fumes. It is an acute condition, meaning its onset is rapid, usually within a few hours of exposure, and its duration is short, typically resolving within 24 to 48 hours without lasting effects. The most common culprit is zinc oxide fumes, but fumes from other metals like magnesium, copper, nickel, manganese, iron, and cadmium can also trigger the condition. It’s not a true infection, but rather an inflammatory response by the body to the inhaled particles.

Historical Context of Metal Fume Fever

The condition has been recognized for centuries, with early descriptions appearing in medical texts related to brass workers, who frequently handled zinc and copper. Its prevalence increased significantly with the industrial revolution and the widespread adoption of welding and other high-temperature metal processing techniques. Despite its long history, awareness among workers and even some medical professionals remains low, leading to ongoing challenges in diagnosis and prevention.

Causes and Mechanisms of Metal Fume Fever

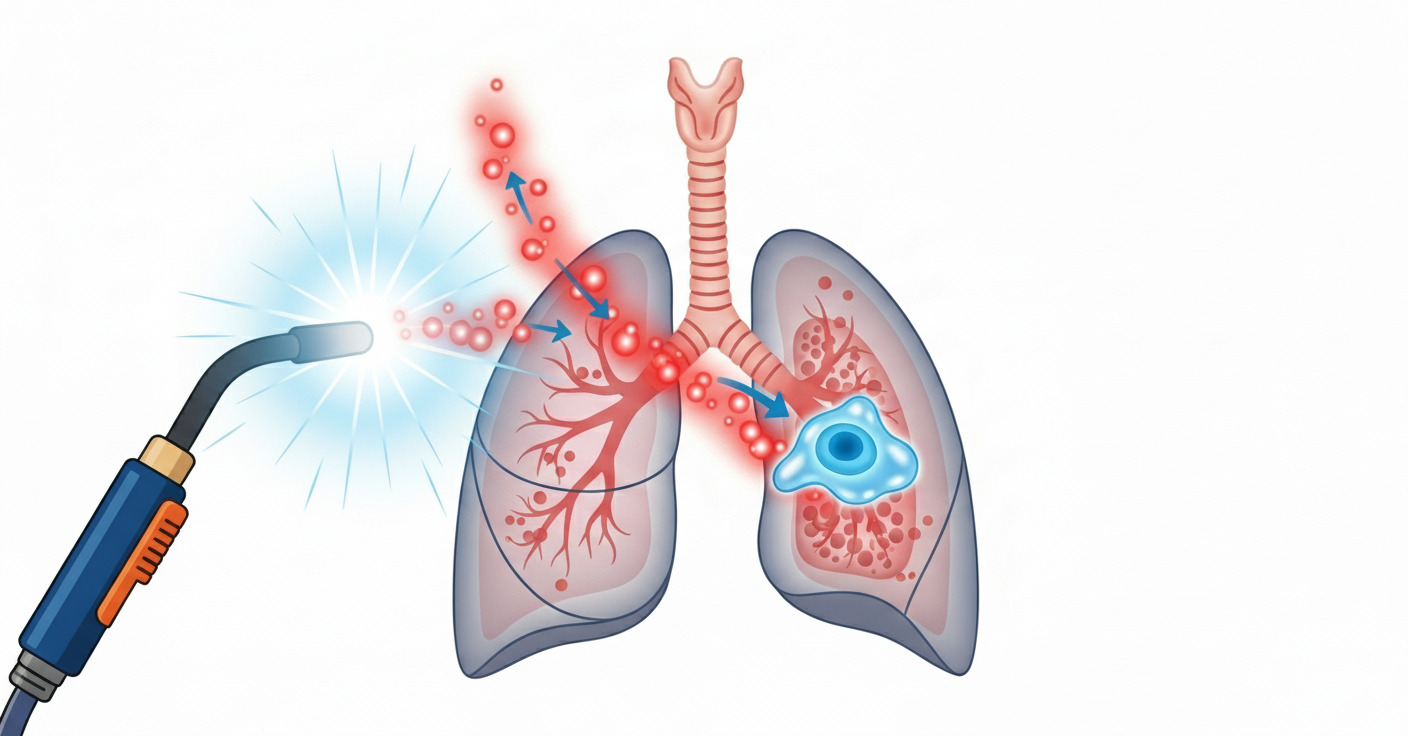

The primary cause of Metal Fume Fever is the inhalation of metal oxide fumes. When metals are heated above their boiling point, they vaporize. These metal vapors then react with oxygen in the air to form extremely fine, respirable metal oxide particles. It is these tiny particles, particularly those in the nanometer range, that are inhaled deep into the lungs and trigger the immune response. This is particularly common in various welding processes, including Shielded Metal Arc Welding (SMAW), Gas Metal Arc Welding (GMAW), and Gas Tungsten Arc Welding (GTAW or Heli-Arc).

Key Metals Involved

- Zinc (ZnO): This is by far the most common cause, often found in galvanized steel, brass, and some welding electrodes.

- Copper (CuO): Present in brass and bronze.

- Magnesium (MgO): Used in various alloys.

- Aluminum (Al₂O₃): Less common but can occur.

- Nickel (NiO): Found in stainless steel and some alloys.

- Manganese (MnO): Present in certain steel alloys and welding fluxes.

- Iron (Fe₂O₃): Can contribute, especially in environments with high iron particulate.

- Cadmium (CdO): Highly toxic and can cause severe symptoms, sometimes distinct from typical MFF.

How Fumes Affect the Body

Upon inhalation, the fine metal oxide particles bypass the body’s upper respiratory defenses and reach the alveoli (air sacs) in the lungs. Here, they are recognized by the immune system, particularly by macrophages, which are scavenger cells. The exact mechanism is still being researched, but it is believed that the metal oxides stimulate these cells to release pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as Interleukin-6 (IL-6) and Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha (TNF-α). These cytokines are chemical messengers that trigger a systemic inflammatory response, leading to the flu-like symptoms characteristic of MFF.

Interestingly, workers can develop a form of tolerance or acclimatization if they are continuously exposed over several days. This means that symptoms may be less severe or even absent after initial exposure, only to reappear after a period away from exposure (e.g., a weekend). This “Monday morning fever” phenomenon is a classic indicator of MFF.

Symptoms of Metal Fume Fever

The symptoms of Metal Fume Fever typically manifest within 4 to 10 hours after exposure, often occurring in the evening after a day’s work. They closely mimic those of the common flu, which is why it’s frequently misdiagnosed. The severity of symptoms usually correlates with the duration and intensity of exposure.

Common Symptoms Include:

- Fever and Chills: A sudden onset of fever, often accompanied by shivering and chills, is the hallmark symptom. The fever can reach 101-104°F (38-40°C).

- Malaise and Fatigue: General feeling of discomfort, tiredness, and weakness.

- Muscle Aches (Myalgia) and Joint Pain (Arthralgia): Widespread body aches, similar to a flu.

- Headache: Often throbbing and persistent.

- Nausea and Vomiting: Gastrointestinal upset can occur in some cases.

- Dry Cough and Chest Tightness: Respiratory symptoms are common, though usually mild.

- Shortness of Breath: Typically mild and temporary.

- Metallic Taste in Mouth: Some individuals report an unusual taste.

- Thirst: Increased thirst can also be present.

One of the most characteristic features of MFF is its self-limiting nature. Symptoms typically peak within 12-24 hours and resolve completely within 48 hours without any specific medical treatment or lasting damage. However, the experience can be very uncomfortable and distressing for the affected individual.

Diagnosis of Metal Fume Fever

Diagnosing Metal Fume Fever is primarily based on a combination of a characteristic occupational history and the presence of typical flu-like symptoms. There is no specific diagnostic test for MFF, making a thorough understanding of the patient’s work environment crucial.

Key Diagnostic Considerations:

- Exposure History: The most important factor is recent exposure (within hours) to metal fumes, particularly from welding, galvanizing, or metal cutting. Asking about the specific materials being worked on (e.g., galvanized steel) is vital.

- Symptom Presentation: The classic flu-like symptoms, especially the “Monday morning fever” phenomenon, are strong indicators.

- Lack of Infectious Cause: Unlike the flu, MFF is not contagious. Blood tests will typically not show elevated white blood cell counts indicative of a bacterial infection, though a transient leukocytosis (increase in white blood cells) can sometimes be observed. Inflammatory markers, such as C-reactive protein (CRP), may be elevated.

- Rapid Resolution: The quick and complete resolution of symptoms without specific treatment is a hallmark of MFF.

It’s important to differentiate MFF from more serious conditions like pneumonia or other forms of metal toxicity (e.g., cadmium poisoning, which can cause severe and prolonged respiratory damage). If symptoms are severe, persistent, or accompanied by significant respiratory distress, further medical evaluation is warranted.

Treatment and Management

As Metal Fume Fever is a self-limiting condition, treatment is primarily supportive and aimed at alleviating symptoms. There is no specific antidote or cure.

Recommended Management Strategies:

- Rest: Getting adequate rest is crucial for recovery.

- Hydration: Drinking plenty of fluids helps prevent dehydration, especially with fever.

- Over-the-Counter Medications:

- Pain relievers and fever reducers: Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) like ibuprofen or acetaminophen (paracetamol) can help manage fever, headache, and muscle aches.

- Avoid Further Exposure: It is imperative to remove the affected individual from the source of metal fumes to prevent worsening of symptoms or recurrence.

Most individuals recover completely within 24-48 hours and can return to work once symptoms have resolved, provided adequate preventive measures are in place to avoid re-exposure.

Prevention of Metal Fume Fever

Prevention is the cornerstone of managing Metal Fume Fever. Since the condition is directly linked to inhaling metal fumes, eliminating or significantly reducing exposure is the most effective strategy. A multi-faceted approach involving engineering controls, administrative controls, and personal protective equipment (PPE) is essential.

1. Engineering Controls (Most Effective)

These methods aim to eliminate or reduce the hazard at its source and are considered the most effective long-term solutions.

Ventilation:

- **Local Exhaust Ventilation (LEV): This is paramount. LEV systems, such as fume extraction guns, capture hoods, or downdraft tables, should be positioned as close to the welding or heating source as possible to draw fumes away from the worker’s breathing zone. For more information on welding ventilation, consider resources like welding ventilation guides.

- General Dilution Ventilation: This involves providing fresh air to the work area and exhausting contaminated air. While helpful, it’s less effective than LEV for point-source fume generation.

Process Modification:

- Substitute Materials: Where possible, use metals or coatings that produce less toxic fumes or no fumes at all. For example, using ungalvanized steel instead of galvanized steel if appropriate.

- Pre-Cleaning: Removing coatings, paints, or rust from metals before heating can significantly reduce the amount and toxicity of fumes generated.

- Lower Temperature Processes: If feasible, using welding or cutting processes that operate at lower temperatures can reduce fume generation.

2. Administrative Controls

These involve changing work practices to reduce exposure.

- Worker Training: Educating workers about the risks of metal fume exposure, the symptoms of MFF, proper use of ventilation, and PPE is critical.

- Work Rotation: Rotating workers in and out of high-fume areas can limit individual exposure times.

- Good Housekeeping: Regularly cleaning work areas to remove settled dust and metal particles prevents their re-suspension and inhalation.

- Medical Surveillance: While not a direct preventive measure for MFF, regular health checks for workers exposed to certain metal fumes (e.g., cadmium) can monitor for long-term health effects.

3. Personal Protective Equipment (PPE)

PPE should be considered the last line of defense when engineering and administrative controls are insufficient or not feasible.

Respiratory Protection:

- Respirators: Appropriate respirators, such as N95 particulate respirators or more advanced powered air-purifying respirators (PAPRs), should be used when fume levels exceed occupational exposure limits. The type of respirator required depends on the specific metals involved and the concentration of fumes. Fit-testing is essential for all tight-fitting respirators.

- Welding Helmets with Integrated Respirators: Many modern welding helmets come with built-in air-purifying respirators, providing both eye/face protection and respiratory protection.

Other PPE: While not directly preventing MFF, other PPE like gloves, flame-retardant clothing, and safety glasses are essential for general worker safety in metalworking environments.

The Importance of Proper Ventilation for Welders

For welders, who are particularly susceptible to MFF, proper ventilation is non-negotiable. Welding fumes are a complex mixture of gases and fine particulate matter, often containing zinc, manganese, iron, and other potentially hazardous substances. The composition can vary significantly depending on the welding process, whether it’s Shielded Metal Arc Welding (SMAW), Gas Metal Arc Welding (GMAW), or Gas Tungsten Arc Welding (GTAW). Inadequate ventilation can lead not only to MFF but also to more serious long-term respiratory problems, including chronic bronchitis, pneumoconiosis, and even certain cancers. Therefore, investing in and consistently using effective welding ventilation systems is a critical safety measure.

Long-Term Effects and Complications

One of the reassuring aspects of Metal Fume Fever is that it is generally considered a benign condition with no known long-term health consequences when exposure is acute and limited. The symptoms resolve completely, and there is no evidence of permanent lung damage or other organ impairment from typical MFF episodes.

Distinction from Other Metal Toxicities:

It is crucial to differentiate MFF from other, more serious forms of metal toxicity that can result from chronic or high-level exposure to certain metals. For instance:

- Cadmium Toxicity: Inhalation of cadmium fumes can cause a severe form of MFF, but prolonged or intense exposure can lead to much more serious and potentially fatal respiratory damage (chemical pneumonitis, pulmonary edema), kidney damage, and bone problems.

- Manganese Toxicity: Chronic exposure to manganese fumes, particularly in welders, is associated with neurological disorders resembling Parkinson’s disease (manganism).

- Lead Toxicity: Lead fumes can lead to systemic lead poisoning affecting multiple organ systems, including the nervous system, kidneys, and blood.

- Beryllium Toxicity: Chronic beryllium disease (CBD) is a serious and potentially fatal lung disease resulting from sensitivity to beryllium exposure.

While MFF itself is not serious, its occurrence signals that workers are being exposed to metal fumes, which could contain these more dangerous elements. Therefore, an MFF diagnosis should always trigger a review of workplace safety practices and exposure controls to ensure broader worker health and safety.

Case Studies and Research

Numerous case studies and research papers have documented the prevalence and characteristics of Metal Fume Fever. These studies often highlight the importance of proper ventilation and PPE.

For example, a study published in the Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine might investigate the incidence of MFF among welders in different industrial settings, correlating symptoms with specific metal exposures and the effectiveness of various control measures.

Final Thoughts

Metal Fume Fever stands as a clear reminder of the potential health hazards present in many industrial settings. While often transient and without lasting effects, it serves as a critical warning sign that workplace exposure controls are inadequate. For employers, prioritizing effective ventilation systems and comprehensive worker training is not just a regulatory requirement but a moral imperative. For workers, understanding the risks, recognizing the symptoms, and diligently using personal protective equipment are essential for safeguarding their health.

Ultimately, a proactive approach focusing on prevention through engineering controls is the most effective way to eliminate the incidence of Metal Fume Fever and ensure a safer working environment for all those who work with metals. By fostering a culture of safety and continuous improvement in industrial hygiene, we can protect workers from this preventable occupational illness.

Amranul is a highly experienced product review writer with a passion for helping readers make smart, informed purchasing decisions. Since 2018, he has specialized in thoroughly researching and analyzing a wide range of products to deliver honest, in-depth reviews. Amranul combines technical accuracy with clear, engaging writing to break down complex product features and highlight true user value. Look for his reviews to find reliable information and expert insights you can trust before you buy!